Ever wondered why some cables cost $2 per meter while others cost $20? Or why your 'heavy-duty' cable failed after six months while a cheaper one lasted five years? The answer lies in construction—the layers and materials inside the cable.

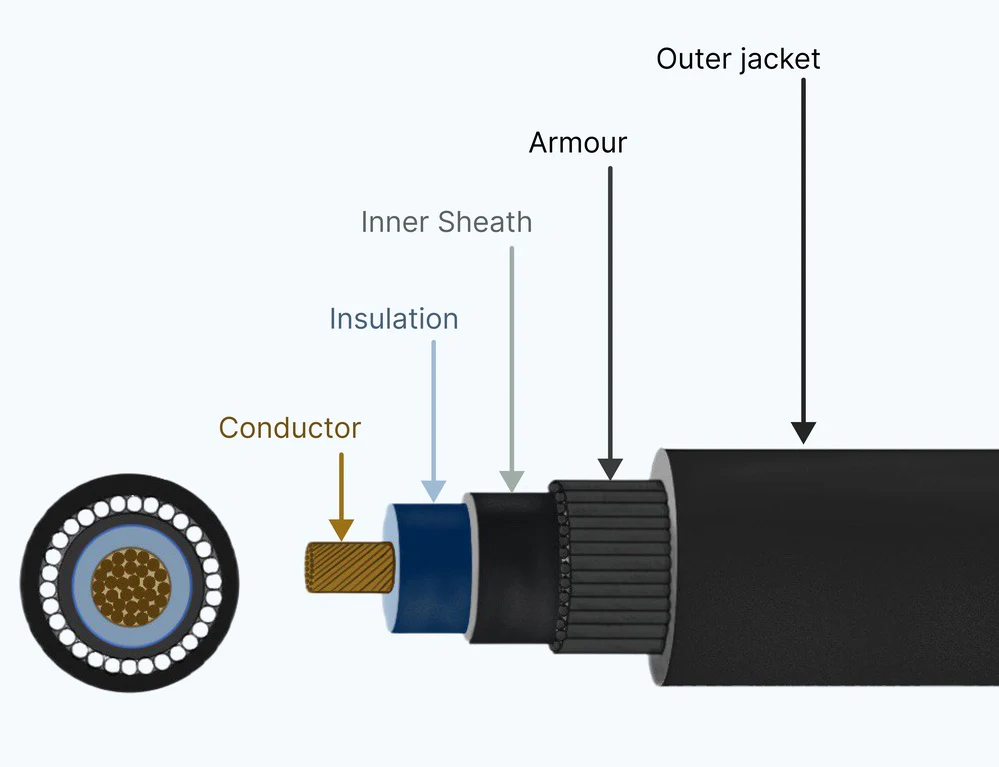

Cable Construction

This guide breaks down cable anatomy layer by layer, explaining what each component does and when it actually matters. No fluff, just practical knowledge for making better cable decisions.

Why Cable Construction Matters

A cable is an engineered system where every layer has a job. Understanding construction helps you:

- Avoid overpaying for features you don't need

- Prevent failures by specifying the right materials

- Compare cables across different manufacturers

- Understand why 'equivalent' cables perform differently

Let's cut open a cable and see what's inside.

Layer 1: The Conductor (Where Current Flows)

The conductor is the metal core that carries electrical current. Everything else exists to protect and insulate it.

Conductor Materials: What's Really Inside

Copper (Standard Choice)

- Best overall conductivity and reliability

- Solderable and widely compatible

- Used in 95% of quality cables

- More expensive than alternatives but worth it

Aluminum

- 40% less conductive than copper (needs larger size for same current)

- Much lighter and cheaper

- Oxidizes easily, requires special connectors

- Best use: Overhead power lines, large feeder cables where weight matters

Copper-Clad Aluminum (CCA) - Avoid This

- Thin copper coating over aluminum core

- Sold as 'copper' in cheap cables

- 30-40% less conductive than real copper

- Fails at connection points when copper layer wears through

- Not code-compliant in most countries

- Red flag: If the price seems too good, it's probably CCA

Tinned Copper (Premium Option)

- Copper wire with thin tin coating

- Prevents corrosion in wet/marine environments

- Easier to solder than bare copper

- Worth the 10-15% premium for outdoor/marine use

Key principle: Never compromise on conductor material. A cheap conductor will cause problems you can't fix later.

Conductor Stranding: Flexibility vs Strength

How the conductor is constructed determines if the cable can bend, flex, or move.

Solid Conductor (Single Wire)

- One thick wire

- Rigid, breaks with repeated bending

- Slightly better current capacity

- Use for: Fixed building wiring in conduit, permanent installations

- Avoid for: Anything that moves or flexes

Stranded Conductor (7-19 strands)

- Multiple wires twisted together

- Moderate flexibility

- Standard for most applications

- Use for: General cables, occasional flexing

- Bend life: 500-2,000 cycles

Flexible Conductor (50-100+ strands)

- Many fine wires bundled together

- High flexibility for repeated bending

- Use for: Power cords, equipment cables, frequent movement

- Bend life: 10,000-50,000 cycles

Extra-Flexible Conductor (1000+ ultra-fine strands)

- Extremely fine wires in specialized construction

- Designed for continuous motion applications

- Significantly more expensive

- Use for: Robot cables, drag chains, cable carriers, coiled cables

- Bend life: 1-5 million cycles

Decision guide:

- Fixed installation = Solid or basic stranded

- Occasional movement = Stranded

- Daily flexing = Flexible

- Continuous motion = Extra-flexible (and budget accordingly)

Conductor Size: Bigger Isn't Always Better

Conductor size determines current capacity, but the relationship isn't simple.

Key factors affecting current capacity:

- Ambient temperature (higher temp = lower capacity)

- Installation method (in conduit vs open air)

- Number of cables bundled together

- Insulation temperature rating

- Continuous vs intermittent use

Example: A 10 AWG (6mm²) copper conductor can carry:

- 30A in conduit with multiple cables (worst case)

- 40A in typical building installation

- 55A in open air, single cable (best case)

Common mistake: Buying cable much larger than needed 'just to be safe.' This wastes money and makes installation harder. Calculate actual requirements or consult load tables.

Layer 2: Insulation (The Critical Barrier)

Insulation prevents electrical shock, short circuits, and environmental damage. Material choice determines where your cable can work and how long it lasts.

Common Insulation Materials Compared

PVC (Polyvinyl Chloride) - The Standard

- Temperature range: -10°C to +70°C

- Cost: Baseline (cheapest)

- Pros: Good electrical properties, flame retardant, low cost

- Cons: Stiff in cold weather, UV degrades it, releases toxic smoke when burning

- Best for: Indoor building wiring, controlled environments, budget applications

- Avoid for: Outdoor use (without UV protection), extreme temperatures, high-flex applications

XLPE (Cross-Linked Polyethylene) - The Upgrade

- Temperature range: -40°C to +90°C

- Cost: 1.5-2x vs PVC

- Pros: Excellent electrical properties, moisture resistant, wide temperature range

- Cons: Not naturally flame-retardant, slightly harder to strip

- Best for: Power distribution, industrial cables, outdoor/underground installations

- Why upgrade: When temperature extremes or moisture are concerns

EPR (Ethylene Propylene Rubber) - The Flexible Option

- Temperature range: -50°C to +90°C

- Cost: 2-2.5x vs PVC

- Pros: Stays flexible in extreme cold, excellent aging resistance

- Cons: Lower abrasion resistance

- Best for: Portable equipment, mining, cold environments

- Why choose: When flexibility in harsh conditions matters

Silicone Rubber - The Extreme Temperature Specialist

- Temperature range: -60°C to +180°C (some to +250°C)

- Cost: 4-6x vs PVC

- Pros: Extreme temperature range, maintains flexibility, flame resistant

- Cons: Lower abrasion resistance, attracts dust, expensive

- Best for: Ovens, kilns, heating elements, aerospace, medical equipment

- Why pay premium: When nothing else handles the temperature

PUR (Polyurethane) - The Tough Performer

- Temperature range: -40°C to +80°C

- Cost: 3-4x vs PVC

- Pros: Excellent abrasion resistance, oil resistant, very durable

- Cons: Can degrade in hot/humid conditions

- Best for: Drag chains, robotics, machine tools, continuous flex

- Why choose: When mechanical abuse is the main concern

Insulation Thickness: More Than Just Voltage

Thicker insulation = higher voltage rating, but also:

- Larger cable diameter

- Less flexibility

- Higher cost

- Harder to terminate

Typical examples:

- 300V application: 0.4mm insulation

- 600V application: 0.8mm insulation

- 1000V application: 1.0mm insulation

Rule of thumb: Use the voltage rating you actually need, not what 'seems safer.' Over-insulated cables cost more and work worse in tight spaces.

Layer 3: Color Coding (Safety First)

Wire colors aren't decorative—they're critical safety markers. But standards vary by country.

Quick Color Code Reference

United States (NEC):

- Ground: Green or Green/Yellow

- Neutral: White or Gray

- Hot: Black (primary), Red, Blue

Europe (IEC):

- Ground: Green/Yellow (mandatory)

- Neutral: Blue

- Phase 1: Brown

- Phase 2: Black

- Phase 3: Gray

China (GB):

- Ground: Green/Yellow

- Neutral: Light Blue

- Phase A: Yellow

- Phase B: Green

- Phase C: Red

Critical safety warning: Never assume colors mean the same thing internationally. A blue wire is neutral in Europe but might be a hot conductor in the US. Always test and verify.

Layer 4: Cable Assembly (How It's Built)

How individual wires are arranged affects performance and size.

Common Configurations

Round Bundle (Most Common)

- All conductors bundled in circular shape

- Easy to work with, familiar to installers

- Larger diameter than alternatives

Twisted Pairs

- Wires twisted together in pairs

- Reduces electromagnetic interference

- Essential for data cables and sensitive signals

- When to use: Any signal or control cable in electrically noisy environments

Flat/Ribbon

- Conductors in flat plane

- Fits under carpets or along surfaces

- Poor mechanical protection

- When to use: Temporary installations, under-carpet wiring

Fillers and Wrapping

Most cables include material between conductors and outer jacket:

Fillers: Fill voids to make round shape, prevent conductor movement Wrapping tape: Holds conductors together during manufacturing

These seem minor but affect:

- How easy the cable is to strip and terminate

- Overall cable roundness and appearance

- Flame rating (different filler materials burn differently)

Layer 5: Shielding (The Interference Blocker)

Shielding blocks electromagnetic interference (EMI). Not all cables need it, but when they do, the type matters.

Do You Actually Need Shielding?

YES, you need shielding for:

- Instrumentation and sensor cables

- Data communication (Ethernet, RS-485, etc.)

- Audio/video cables

- Motor cables near sensitive electronics

- Any cable in electrically noisy environments

NO, skip shielding for:

- Simple power distribution

- Lighting circuits

- Basic on/off control signals

- High-level signals in clean environments

Why it matters: Shielding adds 20-40% to cable cost. Don't pay for it if you don't need it.

Shielding Types Explained

Aluminum Foil (Cheapest)

- Thin aluminum foil wrapped around conductors

- 100% coverage (perfect barrier)

- Excellent for high-frequency interference (radio, WiFi, etc.)

- Fragile, needs careful handling

- Requires drain wire for grounding

- Best for: Fixed installations, data cables, cost-sensitive applications

Copper Braid (Strongest)

- Woven copper wires forming mesh

- 70-95% coverage (small gaps)

- Excellent for low-frequency interference (motors, power lines)

- Mechanically strong, handles flexing well

- Easy to terminate properly

- Best for: Flexible cables, industrial environments, applications with movement

Spiral/Served (Most Flexible)

- Copper wires spiraled around core (not woven)

- 60-85% coverage

- Maintains shield integrity during continuous flexing

- Best for: Robot cables, drag chains, continuous motion applications

Foil + Braid (Premium)

- Both types combined

- 100% coverage + mechanical strength

- Best overall performance (85-100dB shielding effectiveness)

- Most expensive

- Best for: High-EMI environments, sensitive equipment, professional audio

Shield Grounding: The Critical Detail

A shield only works if properly grounded. Two main methods:

Ground at One End Only:

- Prevents ground loops

- Good for long cable runs

- Less effective at high frequencies

- Use when: Cable runs between areas with different ground potentials

Ground at Both Ends:

- Best high-frequency performance

- Can create ground loops if voltage difference exists

- Required by most industrial standards

- Use when: Short runs, same ground reference at both ends

Common mistake: 'Pigtail' grounding (twisting shield into a wire and connecting to a terminal) provides almost no shielding. Always use 360-degree connections with proper shielded connectors.

Layer 6: Armor (Mechanical Protection)

Armor protects against crushing, impacts, and physical damage. Heavy and expensive, so only use when needed.

Armor Types

Steel Wire Armor (SWA)

- Galvanized steel wires wrapped around cable

- Excellent protection against everything

- Heavy, stiff, large bend radius

- Use for: Direct burial, industrial plants, areas with heavy equipment

Steel Tape Armor (STA)

- Two layers of steel tape in opposite directions

- Good protection, more flexible than wire

- Lighter than wire armor

- Use for: Cable trays, moderate mechanical risk areas

Aluminum Armor

- Lighter alternative to steel

- Non-magnetic (important near sensitive instruments)

- Good but not as tough as steel

- Use for: Weight-critical applications, non-magnetic requirements

Interlocked Armor

- Metal strips in interlocking spiral

- Surprisingly flexible despite armor

- Can be coiled and bent

- Use for: Flexible connections that need mechanical protection

When You Actually Need Armor

Required:

- Direct burial in accessible areas

- Cables exposed to mechanical hazards

- Rodent-prone environments

- Some hazardous location installations

Recommended:

- High-traffic areas

- Temporary outdoor installations

- Areas with history of cable damage

Usually unnecessary:

- Cables in conduit (conduit provides protection)

- Indoor fixed installations with proper routing

- Low-voltage signal cables (armor costs more than cable replacement)

Cost reality: Armor adds 50-100% to cable cost and weight. Only specify when mechanical damage risk is real.

Layer 7: Outer Jacket (Environmental Shield)

The jacket is your cable's defense against the outside world. Choose wrong and your cable won't survive its environment.

Jacket Materials: Choose for Your Environment

PVC Jacket (Standard Indoor)

- Temperature: -10°C to +70°C

- UV resistance: Poor (degrades in sunlight)

- Oil resistance: Poor

- Abrasion: Moderate

- Cost: Baseline (cheapest)

- Use for: Indoor installations, protected environments

- Lifespan: 10-20 years indoors, 1-5 years outdoors without UV protection

PE (Polyethylene) Jacket (Outdoor Standard)

- Temperature: -40°C to +80°C

- UV resistance: Excellent (with carbon black)

- Oil resistance: Good

- Abrasion: Good

- Cost: Slightly more than PVC

- Use for: Outdoor cables, direct burial, aerial installation

- Lifespan: 20-30 years outdoors

Neoprene Jacket (Industrial Tough)

- Temperature: -40°C to +90°C

- UV resistance: Good

- Oil resistance: Excellent

- Abrasion: Excellent

- Cost: 2-3x PVC

- Use for: Portable industrial equipment, welding cables, harsh environments

- Lifespan: 15-25 years in harsh conditions

PUR Jacket (Flexibility Champion)

- Temperature: -40°C to +80°C

- UV resistance: Good

- Oil resistance: Excellent

- Abrasion: Excellent (best of common materials)

- Cost: 3-4x PVC

- Use for: Drag chains, robotics, continuous flex applications

- Warning: Can degrade in hot, humid environments (hydrolysis)

- Lifespan: Measured in flex cycles (1-5 million) not years

TPE Jacket (Modern Alternative)

- Temperature: -40°C to +90°C

- UV resistance: Good

- Oil resistance: Good

- Abrasion: Very good

- Cost: 2-3x PVC

- Use for: Portable power cords, flexible applications

- Advantage: Recyclable (unlike rubber)

Silicone Jacket (Extreme Temperature)

- Temperature: -60°C to +180°C

- UV resistance: Excellent

- Oil resistance: Moderate

- Abrasion: Poor

- Cost: 5-7x PVC

- Use for: High-temperature equipment, medical devices, food processing

- Disadvantage: Tacky surface attracts dirt

Special Jacket Properties That Matter

LSZH (Low Smoke Zero Halogen)

- Reduces toxic smoke during fire

- Critical in enclosed spaces (tunnels, ships, aircraft, buildings)

- Usually costs 20-30% more than standard PVC

- Mandatory in many European installations

- When required: Anywhere people might be trapped during fire

UV Resistant

- Essential for any outdoor cable

- Usually achieved with carbon black additive (makes jacket black)

- Failure mode: UV breaks down polymer, causing cracks and brittleness

- Rule: If it sees sunlight, it needs UV protection

Oil and Chemical Resistant

- Critical near machinery, in factories, automotive applications

- Different materials resist different chemicals

- Always specify which chemicals cable will encounter

- Warning: 'Oil resistant' is vague—get specific chemical resistance data

Flame Ratings (North America)

- CM: General indoor use

- CMR: Riser (vertical runs between floors)

- CMP: Plenum (air handling spaces)—most stringent

- Cost impact: CMP costs 2-3x more than CM

- Specify correctly: Using plenum cable everywhere wastes money; using CM in plenum spaces violates code

Putting It Together: Real Cable Examples

Let's decode some real cables to see construction in action.

Example 1: Basic Building Wire

Designation: THHN 12 AWG

Construction:

- Solid or stranded copper conductor (12 AWG = 3.3mm²)

- Thermoplastic (PVC) insulation, heat resistant to 90°C

- Nylon jacket over insulation

- No shielding, no armor

Cost: $0.30-0.50 per meter Use: Fixed indoor building wiring in conduit Lifespan: 30+ years in proper installation

Example 2: Industrial Power Cable

Designation: YJV22 3×25+1×16

Construction:

- Three 25mm² copper conductors + one 16mm² ground

- XLPE (cross-linked polyethylene) insulation

- PVC sheath

- Steel tape armor (22)

- PVC outer jacket

Cost: $8-12 per meter Use: Industrial power distribution, buried or in trays Lifespan: 25-30 years

Example 3: Flexible Control Cable

Designation: LIYCY 8×0.75

Construction:

- Eight flexible copper conductors, 0.75mm² each

- PVC insulation on each conductor

- Copper shield (braided)

- PVC outer jacket

Cost: $2-3 per meter Use: Control signals in industrial automation, sensors Lifespan: 15-20 years fixed, 10-15 years with moderate flexing

Example 4: High-Flex Robot Cable

Designation: ÖLFLEX ROBOT F1 4G6

Construction:

- Four ultra-flexible conductors, 6mm² each (rope-lay, 1000+ strands)

- Special flexible TPE insulation

- Served copper shield (spiral, for flex)

- High-grade PUR jacket

- Precision conductor grouping

Cost: $18-25 per meter Use: Industrial robots, continuous motion applications Lifespan: 5 million flex cycles (2-5 years of continuous operation)

Notice the pattern: Construction complexity and cost scale with application demands. The robot cable costs 60x more than building wire because it's engineered for a completely different job.

How to Specify Cable Construction

When ordering cable, these specifications matter most:

Must Specify (Every Time)

- Conductor material and size - 'Copper, 2.5mm²' not just '2.5mm²'

- Number of conductors - '4 conductor' or '3+ground'

- Voltage rating - '600V' or '0.6/1kV'

- Insulation type - 'PVC' or 'XLPE'

- Jacket material - 'PVC' or 'PUR'

- Application environment - 'Indoor' or 'Outdoor, direct burial'

Specify When Relevant

- Stranding class - Critical for flex applications

- Shielding type - 'Foil' or 'Braid' or 'Unshielded'

- Armor - 'Steel wire armor' if needed

- Temperature range - If outside standard range

- Certifications - 'UL listed' or 'CE marked' if required

- Flame rating - 'Plenum rated' if needed

Don't Over-Specify

- Oxygen-free copper (rarely needed, adds cost)

- Double shielding (unless proven necessary)

- Excessive voltage rating (600V cable for 48V application wastes money)

- Premium features 'just in case' (specify for actual needs)

Cost vs Performance: Making Smart Choices

Understanding construction helps you spend money wisely.

When to Upgrade from Basic Cable

Upgrade conductor stranding when:

- Cable flexes daily (go from solid to stranded)

- Cable moves continuously (go to extra-flexible)

- Installation requires tight bends (flexible conductors needed)

Upgrade insulation when:

- Temperature exceeds 70°C (PVC to XLPE or silicone)

- Moisture is present (PVC to XLPE)

- Chemicals contact cable (PVC to PUR or neoprene)

- Outdoor installation (basic PVC to UV-resistant)

Add shielding when:

- Cable carries signals near power conductors

- Electrical noise causes problems

- Standards require it (industrial networks)

Add armor when:

- Mechanical damage is likely

- Direct burial in accessible areas

- Rodents are a problem

Upgrade jacket when:

- Cable flexes continuously (PVC to PUR or TPE)

- Outdoor/UV exposure (PVC to PE or neoprene)

- Oil/chemical contact (PVC to PUR or neoprene)

- Fire safety critical (standard to LSZH)

When Standard Cable Is Fine

Don't waste money on premium construction when:

- Fixed indoor installation in controlled environment

- No mechanical hazards

- No electrical interference issues

- Temperature stays between 0-50°C

- No chemical or oil exposure

Real example: I've seen installations using $15/meter high-flex cable for fixed installations in control cabinets. Standard $2/meter cable would work perfectly and save 85%.

Common Construction Mistakes (And How to Avoid Them)

Mistake 1: Buying Based on Price Alone

Problem: Cheapest cable often uses CCA conductors or minimal insulation Solution: Always verify conductor material and insulation thickness Cost of mistake: Cable failure within 2-3 years

Mistake 2: Using Indoor Cable Outdoors

Problem: UV degrades non-UV-rated jackets, causing failure Solution: Always specify UV-resistant jacket for any outdoor exposure Cost of mistake: Complete cable replacement in 1-3 years

Mistake 3: Wrong Flexibility for Application

Problem: Using rigid cable where flexing occurs, or paying for high-flex where it's not needed Solution: Match stranding class to actual flex requirements Cost of mistake: Premature failure or wasted money

Mistake 4: Inadequate Temperature Rating

Problem: Using 70°C cable in 90°C environment Solution: Measure actual temperature and add safety margin Cost of mistake: Insulation breakdown, possible fire hazard

Mistake 5: Improper Shield Grounding

Problem: Shield not grounded, grounded at both ends causing ground loops, or pigtail grounding Solution: Follow shielding best practices for your application Cost of mistake: Shield provides no benefit, wasted money

Quick Decision Guide

Use this flowchart approach:

Step 1: Environment

- Indoor, controlled → Standard construction OK

- Outdoor → Need UV-resistant jacket

- Harsh (oil, chemicals) → Need specialized jacket (PUR, neoprene)

- Extreme temperature → Need upgraded insulation (silicone, XLPE)

Step 2: Movement

- Fixed installation → Solid or basic stranded OK

- Occasional flex → Stranded conductor

- Daily flexing → Flexible conductor

- Continuous motion → Extra-flexible, high-flex construction

Step 3: Electrical Environment

- Clean electrical environment → No shielding needed

- Near power lines or motors → Consider shielding

- Data/signal cables → Usually need shielding

- High-EMI environment → Definitely need shielding (possibly double)

Step 4: Mechanical Risk

- Protected installation → No armor needed

- Moderate risk → Consider armor

- Direct burial or heavy equipment area → Armor required

- Extreme abuse → Heavy armor plus protective conduit

Step 5: Safety Requirements

- Standard building → Basic flame rating

- Vertical shafts → Riser rated

- Air handling spaces → Plenum rated

- Enclosed spaces (tunnels, ships) → LSZH required

The Bottom Line

Cable construction is about matching layers and materials to your actual application. Every upgrade costs money, so the key is knowing which upgrades actually matter for your situation.

Three golden rules:

- Never compromise on conductor material - CCA will cause problems. Always use real copper.

- Match insulation and jacket to environment - The right material lasts 10x longer than the wrong material.

- Match flexibility to movement - Don't pay for high-flex where it's not needed, but don't use rigid cable where flexing occurs.

Before you order:

- List your actual operating conditions (temperature, movement, chemicals, EMI, mechanical risks)

- Identify which construction elements address those conditions

- Specify what you need, not what sounds impressive

- Verify the manufacturer can document their construction

A $2 cable correctly specified will outperform and outlast a $10 cable used in the wrong application.

Now you understand what's inside your cables and why it matters. Use this knowledge to specify better, spend smarter, and avoid failures.